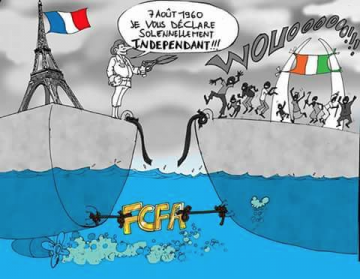

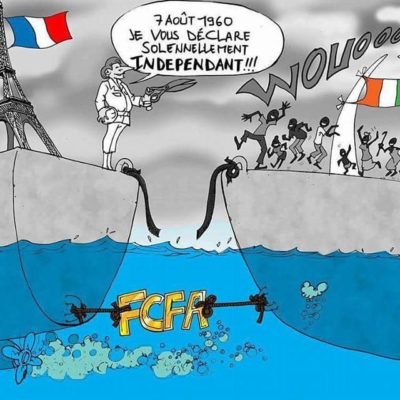

Bustling is the history of the CFA Franc. While some believe that this divisive currency should be resting in the old collections of numismatists fond of colonial history, the CFA franc still runs today in the veins of 14 African economies.

It took a fight between the leaders of two (former) colonial powers to remind us once again of the anomaly of a situation that has been going on for decades.

Last January, Luigi Di Maio, then Vice-President of the Italian Council of Ministers, attacked French President Emmanuel Macron, accusing him of aggravating the migration crisis by continuing to loot Africa. “He first makes the moral, then he[Macron] continues to finance the[French] public debt with the money he plunders from Africa,” he had assailed. For the leader of the 5-star Movement, the means of depredation is none other than the CFA franc, through which Paris “continues to colonize dozens of African countries”.

The French then retaliated by assuring that the attack on Rome was only for internal political purposes. Di Maio’s thesis concerning the CFA franc does not, however, lack arguments: arguments of common sense, arguments of values, arguments by the absurd and, then, the implacable facts of history.

The Italian-French battle is reminiscent of the 1900s. By that time, the colonial powers had completed sharing Africa and deploying their currencies. Africans who had initially adapted their traditional payment methods to the colonizers’ systems had ended up, by the middle of the 20th century, totally abandoning their currencies in favour of francs, marks and shillings.

This history of colonial currencies is told by Régis Antoine, a university specialist in colonial studies, in review of Historia published in February 1988. In his article, the French academic goes back to the early days of Portuguese colonization in Africa and Asia, before going through the centuries. In his journey through time and space, he does not fail to recount the most surprising assaults of the Caribbean freebooters and the most cruel lootings, such as the looting of the treasure of the Dey d’Alger, during the capture of the city by the French colonizers in 1830.

Régis Antoine also recounts the competition between European colonizers to impose their respective currencies on African colonies. Thus the French franc had to face the English shilling in Dahomey[present-day Benin], which had been a territory invested mainly by British traders. In the Kamerun colony lost by Berlin following its defeat in the First World War, French copper-nickel coins had ousted the German marks in just a few months.

In the generalized colonial outbreak of the 1900s, he wrote, the rupees of Queen Victoria, the African pfennigs of William II, the colonial reis of Portugal, the francs of French Africa and the centesimi of Italian Africa, the Belgian francs of Leopold, finally the king of the independent state of Congo (sic) circulate the buns of the rulers and the helmets of the kaisers, the effigies of white republics, the portraits of navigators and peacekeepers.

Of this blatant cavalcade, it was the French franc that had best survived the hecatomb of the two World Wars and the decolonization waves of the 1960s.

Indeed, the CFA franc, or franc of the French Colonies of Africa, as well as the franc of the French Colonies of the Pacific (CFP franc) had been created on 25 December 1945. As a result of the devaluation of the metropolitan franc, the two new currencies enabled the city to revive its ruined economy by continuing to draw comfortably on the rich soil of its colonies for its raw materials.

The metropolitan franc thus devalued against the two new colonial currencies forced the colonies to import cheap products from the metropolis.

A few years later, forced to bend to the irreversible course of history, the French government had not given everything to the countries that were to gain sovereignty. Thus, on the economic and monetary level, Paris had done everything to keep maximum control over its former colonies. A change in the name of the CFA franc had made it possible, among other things, to preserve France’s colonial privileges and the franc zone had remained hermetically sealed.

Today, the CFA franc is no longer the franc of the French Colonies of Africa.

In the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), composed of Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo, the acronym CFA is formed by the initials of the African Financial Community.

And in the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), which includes Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Chad, the CFA franc is called the franc of Financial Cooperation in Central Africa.

A dossier on the Bank of Central African States (BEAC) published in the weekly magazine Jeune Afrique in March 1982 sets out the mechanism for the CEMAC zone issuing institution to be subject to the French Treasury.

Indeed, in accordance with the monetary cooperation agreements signed on 22 and 23 November 1972 in Brazzaville by the BREAC Member States, among themselves and with Paris, the value of the CFA franc is determined in relation to the value of the French franc. In addition, this parity is fixed. Thus, 1 CFA franc was worth 0.02 French francs on that date. Since the creation of the currency of economic and monetary union, formed within the European Union in 1999, 1 euro has been worth 655.957 CFA francs.

Apart from this fixed parity, there are no restrictions on capital movements and current transactions. This is the principle of free transfer, to which is added a third attribute: unlimited convertibility.

So what is the counterpart of these three principles?

“In order to ensure the value of their common currency,” says Jeune Afrique, “BEAC member states agreed in Brazzaville to pool their foreign exchange reserves (foreign exchange and gold reserves are the guarantees of a currency) and deposit them in a current account with the French Treasury, called the operating account. This is a pledge of the unlimited guarantee given by France to the currency issued by BEAC”.

The French Treasury is an agency responsible for managing the State’s debt and cash position.

“The convertibility,” explains the pan-African weekly, “between the CFA franc and the French franc resulting from this guarantee is automatically done through this operating account: it records capital movements linked to international transactions between the BEAC zone and abroad. The conversion of the CFA franc into currencies (foreign currencies) and vice versa is done automatically through the fixed parity linking it to the French franc.

More on the Franc CFA with Hannah Cross: The new monetary policy consensus and the CFA Franc: a labour-focused approach. [Podcast/Eng]

If this dossier entitled “Let’s get to know the BEAC”, which could well apply to BCEAO; the UEMOA central bank, seems to adopt a technical vocabulary coupled with the lexical field of guarantee, stability and insurance, Fanny Pigeaud and Ndongo Samba Sylla’s book, on the other hand, is a vibrant account. L’arme invisible de la Françafrique, a story of the CFA franc that the two authors (a journalist and an economist) presented on 6 November in Tunis is a book that combines history, economics, geopolitics and journalism to explain not the functioning of a currency but the workings of a neo-colonial political economy system. A system that maintains the African economies’ staggering debt burden while depriving them of any room for manoeuvre when designing public policies.

The book, which dates back to the pre-colonial period, is almost sonorous, you can almost hear the sound of drums and the banging of boots of French soldiers in the plains of Upper Volta and along the beaches of Côte d’Ivoire. It emanates from it the echo of the voice muffled in blood, of Sylvanus Olympio, President of Togo and Thomas Sankara, President of the National Revolutionary Council of Burkina Faso. The two men, like countless African voices, had dared to challenge France’s control over the continent and its people.

Through the two hundred pages of the book published in September 2018 by La Découverte, it is not difficult to imagine the French Treasury’s safes full of gold and currency bullion and the empty boxes in Bangui, Niamey or Bamako. It is also possible to see the large, noisy, overcrowded and underdeveloped African cities, in contrast to the opulence of the French metropolises.

What about the future of the CFA franc? The answer is certainly not easy. But what is certain is that the next episode of the saga will be largely written by the 160 million Africans who seem increasingly aware of their rights to sovereignty and prosperity.