By Mohamed Haddad, editor in chief & Khansa Ben Tarjem, President of Barr al Aman.

“Can we sell more olive oil in Europe? Can we mention that it is a product coming from Tunisia? Would it be possible to postpone the next negotiation meeting? What guarantees do we have that our business owners and investors will be allowed on the European territory?”

These few questions may seem simplistic, and obviously caricatural… but they eventually sum up, in a nutshell, the Tunisian negotiators discourse.

Swapping dates, oranges and olive oil for Euros, but what is the counterpart? Where will the thousand tons of wheat consumed by Tunisian households in the form of subsidized baguettes and flour come from? What should the agricultural sector serve for? feed the local population or increase the foreign currency reserves? Should the right to healthcare take precedence over the intellectual property rights and the profits they generate for pharmaceutical companies?

These fundamental questions do not seem to be part of the Tunisian negotiators’ preoccupations. Is this an exaggerated statement? Perhaps.

At the risk of recalling the obvious, the European Union is Tunisia’s first trade partner. But the EU is by no means a charity organization. It is an economic and political entity, one of the most powerful in the world, which position is being threatened by the USA and China.

It is both predictable and legitimate that the EU defends its economic interests and its sphere of political influence in the region. And it should be the same for Tunisia. Interests of these actors can converge… but they can diverge as well.

It is not a question of discussing the modalities and extent of deeper free trade with the EU, but of assessing the balance of power and the impact of each article, each paragraph of this agreement on the lives of citizens, but also of the Tunisian State. As Ignacio Garcio Bercero, chief negotiator of the EU, states, Tunisia represents only 0.5% of the European market, while the European market represents more than 70% of Tunisian exports.

Why taking as much interest in Tunisia, then? Why didn’t the negotiation take place at a the Maghreb scale in order to reduce the lack of proportion between the negotiating parties? Indeed, Tunisia is in a relationship of economic and political dependence on the EU. Would Tunisia be able to re-balance or even… better negotiate its dependence?

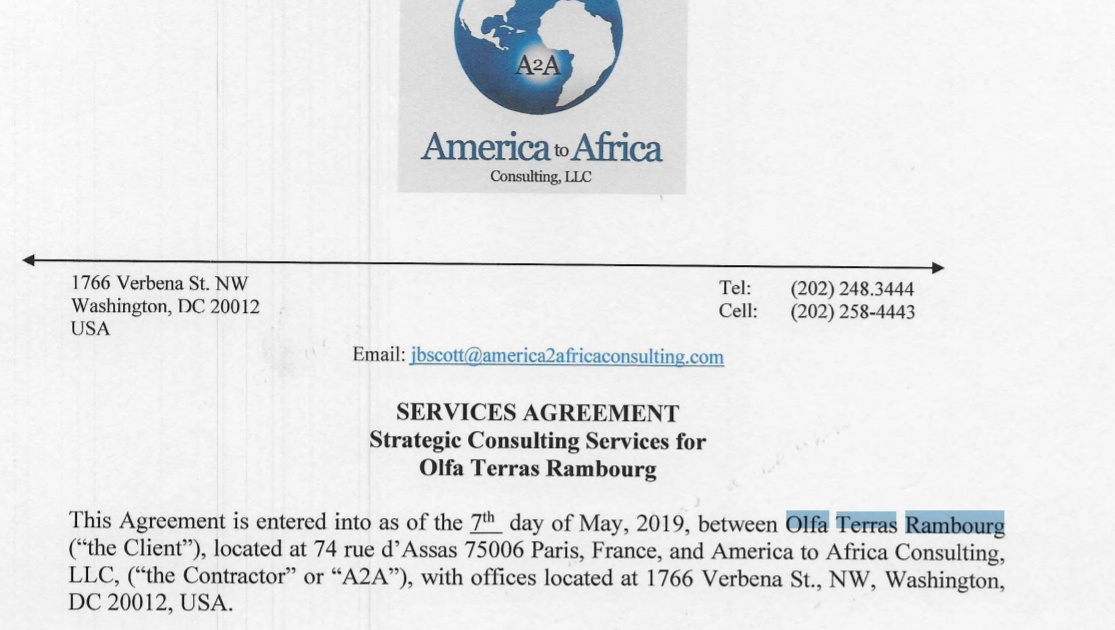

The EU and Tunisia are bound by an association agreement since 1995. What conclusion can we draw from it? The evaluation on Tunisia’s part is dragging. The terms of reference used to choose a consulting cabinet were published in January 2017. Selected at the end of 2018, it is barely starting its work just as this article is being written. Our requests to access information about the final interim reports remain unanswered.

In this series of article about DCFTA, we will first address the ongoing negotiations, happening in the dark. They are the fruit of an investigation led by Fadil Aliriza after a conference by the Tunisian Forum on Economic and Social Rights (FTDES) held in October 2018.

Thereafter, we will concentrate on the topics of food security and sovereignty. The third article will focus on the fragile balance between the right to life and health and the right to intellectual property, a balance which might be challenged by the DCFTA.

Our demands since October 2018 to meet the Tunisian chief negotiator, Hichem Ben Ahmed, currently Minister of Transport remained fruitless. His European counterpart, Ignacio Garcio Bercero, chose to answer our questions by email.

Finally, the critical perspective is raised to us by Maha Ben Gadha, head of the economic programs at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation – North Africa. Beyond these articles, our media, Barr al Aman, will produce meetings and Facebook lives to assess these embryonic public policies.

Let us imagine a private, parallel and transnational justice to defend the interests of investors considered “not enough protected” by Tunisian laws. Let us imagine medicines whose production and marketing were prohibited because of extensions in protection periods, additional to those originally planned by the patent.

Let us imagine calibrated, certified, imported and European-norm-compliant potatoes in our supermarkets. Let us imagine an adaptation of our job market to European expectations…

The Deep Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) proposed to Tunisia by the EU certainly has an advantage: it questions us about who we are, and what we want to be.

Translated by An Hoang-Xuan